Best Private Jet Options: A Definitive Guide to Fleet & Access in 2026

The pursuit of the best private jet options in the current aviation landscape is no longer a simple exercise in comparing cabin dimensions or maximum nautical range. As the industry moves into 2026, the criteria for “best” have bifurcated into two distinct streams: the engineering prowess of the aircraft itself and the structural efficiency of the access model chosen by the flyer. The modern principal must navigate a market where a supersonic pedigree—exemplified by the newly entering Bombardier Global 8000—exists alongside increasingly sophisticated fractional and card-based programs that prioritize operational resilience over hull ownership.

Selecting the optimal path through this sector requires a departure from the “bigger is better” fallacy. A Gulfstream G800 may offer the longest range in the history of business aviation, but if the majority of one’s missions are regional hops between London and Geneva, the aircraft becomes a liability in terms of fuel burn and landing flexibility. Conversely, relying on light-jet charters for transcontinental needs introduces a layer of fatigue and logistical stops that undermines the primary value proposition of private flight: the preservation of time and cognitive energy.

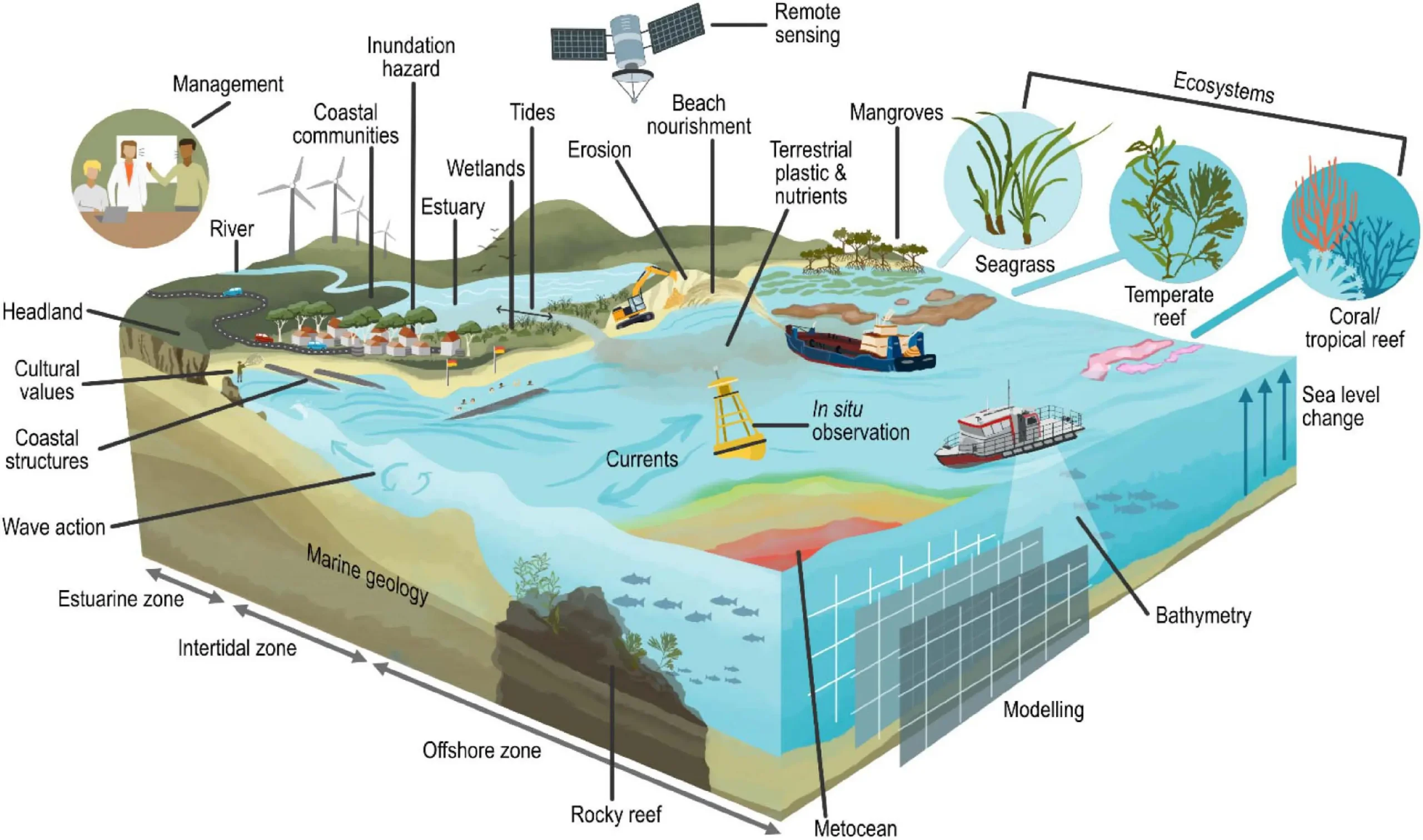

This analysis moves beyond the marketing veneer of private aviation to examine the systemic realities of the fleet. We will explore how geopolitical shifts, sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) mandates, and supply chain constraints have altered the traditional cost-benefit analysis of aircraft acquisition. The goal is to provide a definitive framework for evaluating private flight—not as a luxury indulgence, but as a strategic tool for global mobility.

Understanding “best private jet options”

To evaluate the best private jet options, one must recognize that “best” is a moving target defined by the mission profile. A common misunderstanding in the sector is the belief that performance specifications—such as a top speed of Mach 0.95 or a range of 8,000 nautical miles—are universal indicators of quality. In reality, these are specific tools designed for specific problems. The Global 8000, for instance, solves the “Singapore-to-New York nonstop” problem, but it is an inefficient tool for the “Boston-to-Nantucket” problem, where a turboprop like the Pilatus PC-12 offers superior runway access and lower carbon intensity.

The oversimplification risk often occurs during the transition from charter to ownership. Many users assume that owning the “best” aircraft will solve scheduling issues. However, the best aircraft is useless without a “best-in-class” management structure. Ownership introduces a complex web of crew retention, hangarage, and regulatory compliance that can actually reduce a flyer’s flexibility if not managed by a Tier-1 operator. Thus, the “option” being selected is not just a tail number, but an entire service ecosystem.

Furthermore, the landscape of 2026 has introduced a new variable: the sustainability tax. In regions like Europe, the best option is increasingly defined by its SAF (Sustainable Aviation Fuel) compatibility and its noise-abatement profile. A loud legacy jet and fuel-inefficient aircraft may find themselves banned from certain secondary airports or subject to “solidarity taxes” that exceed $2,000 per departure. Therefore, modern evaluations must account for the regulatory longevity of the airframe, not just its current leather upholstery.

Historical and Systemic Evolution of the Fleet

The private aviation industry has transitioned through three major eras. The first was the era of the “converted airliner,” where corporate flight was a literal extension of commercial aviation, often utilizing modified Boeing or Douglas craft. This was followed by the “purpose-built” era of the late 20th century, which saw the rise of the iconic Learjets and the early Gulfstream series. These were aircraft designed from the ground up for the specific needs of executive speed and privacy.

The current era, beginning in the early 2020s and maturing in 2026, is the “wellness and connectivity” era. The focus has shifted from the cockpit to the cabin. Advancements in pressurization technology now allow ultra-long-range jets to maintain a cabin altitude of just 2,900 feet while cruising at 41,000 feet. This represents a systemic leap in human performance; travellers no longer arrive at their destinations with the “brain fog” associated with high-altitude hypoxia.

Systemically, the fleet has also seen a “digital twin” evolution. Modern aircraft are now constantly streaming data back to the manufacturer. This allows for predictive maintenance, where a part is identified for replacement before it ever fails. This shift from reactive to proactive maintenance has significantly increased dispatch reliability, making the newest generation of jets—such as the Bombardier Global 7500 and the Gulfstream G700—the safest and most reliable options in history.

Conceptual Frameworks for Mission Profiling

Choosing among the best private jet options requires a mental model that prioritizes utility over prestige. Three frameworks are particularly effective:

1. The 80/20 Rule of Range

A flyer should choose an aircraft based on the mission they perform 80% of the time, not the 20% “outlier” mission. If you fly domestically four days a week and internationally once a month, owning a heavy jet is a waste of capital. The strategic move is to own or fractionally own a midsize jet for the 80% and use on-demand charter for the 20% international legs.

2. The Total Wellness Metric

This model evaluates a jet based on its impact on the passenger’s biology.

-

Low Cabin Altitude: Does the jet stay below 4,000 ft effective altitude?

-

Circadian Lighting: Does the lighting system sync with the Flight Management System to mitigate jet lag?

-

Humidity Control: Does the aircraft have active humidification to prevent dehydration?

3. The Runway-to-Office Speed

This framework measures the time from “home door” to “meeting door.” A smaller jet that can land at a tiny municipal airport 5 minutes from your office is “faster” than a massive jet that has to land at a major international hub 60 minutes away, regardless of the air speed.

Key Categories and Variation Trade-offs

The private jet market is segmented by weight, range, and cabin volume. Each category represents a specific trade-off between access and comfort.

| Category | Typical Range (NM) | Pax | Examples | Primary Trade-off |

| Turboprop | 1,500 – 1,800 | 6-9 | Pilatus PC-12, King Air 350i | High access (short/grass strips) vs. slower speed. |

| Light Jet | 1,200 – 2,000 | 4-7 | Phenom 300E, Citation CJ4 | Low operating cost vs. limited cabin height. |

| Midsize | 2,000 – 3,000 | 7-9 | Citation Latitude, Praetor 500 | Transcontinental capability vs. limited baggage. |

| Super-Midsize | 3,000 – 4,000 | 8-10 | Challenger 3500, G280 | “Goldilocks” balance of range/cost vs. high demand. |

| Large/Heavy | 4,000 – 6,000 | 10-16 | Falcon 8X, Gulfstream G550 | Standing room/full galley vs. high fuel burn. |

| Ultra-Long-Range | 7,000 – 8,200 | 13-19 | Global 8000, G700/G800 | Global nonstop reach vs. maximum capital outlay. |

Decision Logic: Acquisition vs. Access

The current market suggests that for under 50 hours of flight per year, on-demand charter is the only logical choice. Between 50 and 200 hours, fractional ownership (e.g., NetJets or Flexjet) or jet cards (e.g., Sentient Jet) provide the best balance of guaranteed availability and cost. Full ownership generally only becomes fiscally defensible above 200–250 hours of annual flight.

Real-World Scenarios and Decision Logic

Scenario A: The Multi-City “Roadshow”

A venture capital team needs to visit six cities in three days (e.g., SF, Austin, Chicago, NYC, Boston, DC).

-

Optimal Option: A Super-Midsize jet like the Challenger 3500. It offers the speed to hit three cities in a day and a cabin spacious enough to serve as a mobile office for the team.

-

Failure Mode: Attempting this with a Light Jet might save money, but the lack of “standing room” and limited Wi-Fi bandwidth will degrade the team’s productivity over the 72 hours.

Scenario B: The Transatlantic Family Relocation

A family of five, including pets and significant luggage, is moving from London to Los Angeles.

-

Optimal Option: An Ultra-Long-Range jet (G650ER or Global 7500). The direct flight (approx. 11 hours) avoids the stress of a fuel stop in Goose Bay or Bangor.

-

Constraint: Luggage volume. While many jets claim “14 passengers,” their baggage holds are often calibrated for executive briefcases, not 15 full-sized suitcases.

Scenario C: The Short-Field Destination

Landing at a high-altitude or short-runway airport (e.g., Aspen, St. Moritz, or a private island strip).

-

Optimal Option: The Pilatus PC-24, known as the “Super Versatile Jet.” It combines the speed of a jet with the short-field performance of a turboprop.

-

Second-Order Effect: Using the “wrong” jet for these airports often results in “payload restrictions,” meaning you can land there, but you can’t take off with a full tank of fuel, necessitating an immediate stop elsewhere.

Cost Dynamics and Resource Allocation

Understanding the best private jet options requires a deep dive into the “hidden” costs of aviation. The sticker price of a jet is merely the entry fee.

| Expense Type | Estimated Range (Annual/Hourly) | Nuance |

| Acquisition (New) | $5M (Light) – $80M (ULR) | Depreciation averages 10-15% in the first 2 years. |

| Fixed Costs (Crew/Hangar) | $500k – $1.5M | Crew salaries have spiked 20% due to pilot shortages. |

| Variable (Fuel/Maintenance) | $2,000 – $6,000 / hour | Fuel prices are highly volatile; SAF carries a premium. |

| Management Fees | $100k – $250k | Covers dispatch, compliance, and training. |

Opportunity Cost and Liquidity

Ownership ties up massive amounts of capital. Many modern HNWIs (High-Net-Worth Individuals) are moving toward “Asset Light” models—fractional shares or long-term leases—to keep that capital deployed in higher-yield investments while still enjoying the operational benefits of a dedicated fleet.

Tools, Strategies, and Support Systems

For those navigating the fleet, several strategic layers are essential:

-

Independent Acquisition Consultants: Never buy a jet from the manufacturer without an independent broker who knows the “off-market” inventory and real-world delivery delays.

-

Safety Audits (ARGUS/Wyvern): These are the gold standards for evaluating operators. Never step on a plane that doesn’t meet at least a “Gold” or “Wingman” rating.

-

Jet Card Agnosticism: Avoid being “locked in” to one provider. High-end flyers often hold a “backup” card with a different operator to ensure coverage during peak holiday blackout dates.

-

Carbon Offset Integration: For corporate fleets, integrated software that tracks emissions per leg and automatically buys offsets is now a standard requirement for ESG compliance.

-

Technical Pre-Buy Inspections: A “clean” logbook is not enough. A deep borescope inspection of the engines can reveal millions of dollars in upcoming maintenance that a casual observer would miss.

Risk Landscape and Failure Modes

The “best” option can quickly become the worst if these risks are not mitigated:

-

The Pilot Shortage: The biggest risk in 2026 is not the aircraft failing, but the lack of a qualified crew. Small, independent operators are losing pilots to major airlines, leading to last-minute cancellations.

-

Maintenance “Grounded” Risk: Parts for older aircraft (e.g., legacy Falcons or Hawkers) are becoming harder to source due to fractured supply chains. An aircraft can be “AOG” (Aircraft on Ground) for weeks waiting for a single sensor.

-

Regulatory Stranding: Buying a jet that doesn’t meet the latest NextGen avionics requirements (like ADS-B Out or FANS-1/A) will render the aircraft unable to fly in most desirable airspace.

-

Charter Broker “Ghosting”: Low-tier brokers often don’t “hold” the aircraft. They take your money, and then the owner of the jet takes a better offer, leaving you stranded.

Governance, Maintenance, and Long-Term Adaptation

A private aviation strategy must evolve. The aircraft you needed as a growth-stage CEO is not the aircraft you need as a board chairman.

The 3-Year Review Cycle

Every 36 months, an owner or frequent flyer should conduct a “Mission Audit.“

-

Step 1: Analyze the last 100 legs flown. What was the average passenger count? Average distance?

-

Step 2: Compare the cost of current access vs. the market. Is the fractional provider’s “Management Fee” still competitive?

-

Step 3: Evaluate the “Exit Strategy.” For owned aircraft, what is the current resale value relative to the upcoming “C-Check” maintenance cost?

Common Misconceptions and Oversimplifications

-

“Newer is always safer”: A well-maintained 10-year-old Gulfstream with a veteran crew is often safer than a brand-new jet operated by a “budget” charter firm.

-

“Empty legs are a great way to fly.: Empty legs are incredibly unreliable. If the “primary” flyer changes their mind, your flight is cancelled instantly. They are for leisure, never for business.

-

“Private jets can land anywhere”: Weight and runway length are hard physical limits. A Global 7500 cannot land on a short island strip meant for a King Air.

-

“It’s faster because of the speed of the plane.: It’s faster because you spend zero minutes in security and 100% of your time flying to the airport closest to your destination.

-

“Buying a jet is a tax write-off”: Only if the mission is strictly for business and meets rigorous IRS (or local authority) “ordinary and necessary” tests.

Synthesis and Final Editorial Judgment

The best private jet options for the current era are those that prioritize the integration of the human and the machine. We have reached a point of “diminishing returns” on raw speed; the difference between Mach 0.85 and Mach 0.90 is negligible on a four-hour flight. The real victory is won in the cabin altitude, the silence of the engines, and the reliability of the global support network.

For the modern principal, the most “luxurious” option is the one that requires the least amount of their attention. This often points away from the ego-driven pride of full ownership and toward the operational sophistication of top-tier fractional programs. By outsourcing the risk of crew management and maintenance to a global-scale operator, the flyer achieves the ultimate goal of private aviation: a life without friction. In the final analysis, the best jet is not the one with the most gold-plated faucets, but the one that is waiting for you on the tarmac, fueled and ready, exactly when the meeting ends.